Joshua Peck served in the Continental Army

It is likely that this is Joshua Peck who

arrived in United States in 1774 from England, settling in Maryland. He was born

in England, and listed on his emigration forms that he was a hairdresser. He was 18 when he left England.

This is reinforced by the fact that the

Governor of Maryland issued a decree that if servants joined the Army to fight

against the British, they would be released from their obligations.

It seems that poor Joshua Peck, arrived at

Maryland at the wrong time, and sensing his freedom, agreed to fight a war

against the British Forces!

He served for 3 years.

The Proclamation was delivered in Virginia, but printed in all

newspapers.

... I do require every Person capable of bearing Arms, to resort

to His MAJESTY'S STANDARD, or be looked upon as Traitors to His MAJESTY'S Crown

and Government, and thereby become liable to the Penalty the Law inflicts upon

such Offenses; such as forfeiture of Life, confiscation of Lands, &. &.

And I do hereby further declare all indented Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to

Rebels,) free that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His

MAJESTY'S Troops as soon as may be, for the more speedily reducing this Colony

to a proper Sense of their Duty, to His MAJESTY'S Crown and Dignity.

— Lord Dunmore's Proclamation, November 7, 1775

There

are no further US records for this Joshua Peck.

They British Army lost the war, and thousands died.

The Continental Army

- Overview

The Continental

Army was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the former British

colonies that later

became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the

Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of

the Thirteen Colonies in their ultimately successful

revolt against British rule. The Continental Army was

supplemented by local militias and volunteer troops that remained

under control of the individual states or were otherwise independent.

General George Washington was the commander-in-chief of the

army throughout the war.

Most of the

Continental Army was disbanded in 1783 after the Treaty of Paris formally ended the war. The 1st

and 2nd Regiments went on to form the nucleus of the Legion of the United States in 1792 under General Anthony

Wayne. This became the

foundation of the United States Army in 1796.

Lee's Additional Continental Regiment was raised on January 12, 1777 with troops from Massachusetts at Cambridge, Massachusetts for service with the Continental Army. The regiment was commanded by Colonel William R. Lee, and saw action at the Battle of Monmouth and the Battle of Rhode Island. The Regiment was merged into the 16th Massachusetts Regiment on April 9, 1779. Its lineage is perpetuated by the 101st Engineer Battalion

The 3rd Regiment of the

Continental Army 1776

Joshua Peck was in the 3rd Regiment of the

Continental Army.

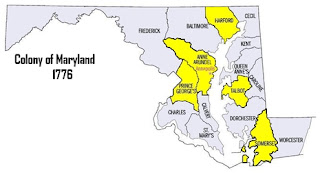

The 3rd Maryland Regiment was organized on 27 March 1776 of

eight companies from Anne Arundel, Prince George's, Talbot, Harford and Somerset counties of the colony of Maryland.

The regiment was authorized on 16 September 1776 for service

with the Continental Army and was assigned on 27 December 1776 to the main element

1st Maryland Brigade

On 22 May 1777 it was assigned to the 1st Maryland

Brigade. The regiment was re-organized to nine companies on 12 May 1779. On

5 April 1780 the 1st Maryland Brigade was reassigned to

the Southern Department. The regiment was

relieved from the 1st Maryland Brigade on 1 January 1781. It

was assigned to Gist's Brigade on 24 September 1781 in the

main Continental Army. Three days later (27 September 1781) Gist's Brigade was

reassigned to the Southern Department. On 4 January 1782

the regiment was reassigned from Gist's Brigade to the Maryland

Brigade in the Southern Department. The regiment

would see action during the Battle of Brandywine, Battle of Germantown, Battle of Monmouth, Battle of Camden, Battle of Guilford Court House, Battle of Eutaw Springs and the Battle of Yorktown. The regiment disbanded on 1 January 1783 at Charleston, South Carolina.

Under Gist's command

Gist became colonel in command of the 3rd Maryland on 10

December 1776. On 22 May 1777, George Washington assigned the

regiment to the 1st Maryland Brigade together with the 1st Delaware Regiment, and the 1st, 5th, 7th Maryland Regiments. During the Battle of Brandywine on 11 September 1777, both the popular brigade

commander William Smallwood and Gist were on detached duty recruiting the Maryland

militia. This left the disliked Frenchman Philippe Hubert Preudhomme de Borre as the senior

brigadier. The regiment was in John Sullivan's division on the right flank, guarding Brinton's Ford while

other elements of the division guarded three upstream fords. Finding that

the greater part of Sir William Howe's army had marched into the right rear of his division,

Sullivan had to march cross country in an attempt to block the move. Finding

his division in an awkward position, Sullivan rode off to confer with Adam Stephen and Lord Stirling and ordered De Borre to shift the division to the right.

The inept Frenchman botched the evolution, throwing the troops

into disorder just as they came under attack by the Brigade of Guards. According

to John Hoskins Stone, commander of the 1st Maryland, only his regiment and the 3rd

put up a creditable fight. As they tried to resist the oncoming British, the

confused 2nd Brigade mistakenly fired a volley into the two regiments from

behind. The badly mishandled Marylanders then fled.

Gist commanded the 3rd Maryland at the Battle of Germantown. He led the 3rd Maryland until 9 January 1779 when he was

promoted brigadier general in command of the 2nd Maryland Brigade.

Battle of Monmouth

At Monmouth, the regiment was commanded by Colonel Mordecai Gist while its

second-in-command was Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel Ramsey. Ramsey was

detached to Colonel James Wesson's detachment under Brigadier General Anthony Wayne. Early in the

battle, Wesson was wounded and Ramsey assumed command of his

detachment. Surprised by a sudden British counterattack, the American

advance guard began to retreat.

Washington personally asked Ramsey and Colonel Walter Stewart to hold off the British while he arranged the main line of

defence. The two officers agreed and Wayne deployed their soldiers in a nearby

wood. As the Brigade of Guards came up to their hidden position, the

Americans opened fire into their flank. The Guards charged and cleared the wood

after a tough fight in which they lost 40 casualties including Colonel Henry

Trelawney wounded. Stewart was shot and carried off. The retreating Americans

were set upon in the open by a troop of the 16th Light Dragoons. A dragoon rode up to the unhorsed Ramsey and fired at him

with his pistol. The weapon misfired and Ramsey attacked the trooper with his

sword, dragged him from his horse, and tried to ride away.

Surrounded by dragoons, Ramsey was badly wounded and left for

dead. Later, the British picked him up as a prisoner. Impressed by his bravery,

the British commander Sir Henry Clinton paroled

Ramsey the next day. Ramsey was not exchanged until December 1780.

Gist commanded the 3rd Maryland at the Battle of Germantown. He led the 3rd Maryland until 9 January 1779 when he was

promoted brigadier general in command of the 2nd Maryland Brigade.[1]

Battle of Monmouth

At Monmouth, the regiment was commanded by Colonel Mordecai Gist while its

second-in-command was Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel Ramsey. Ramsey was

detached to Colonel James Wesson's detachment under Brigadier General Anthony Wayne. Early in the

battle, Wesson was wounded and Ramsey assumed command of his

detachment. Surprised by a sudden British counterattack, the American

advance guard began to retreat.

Washington personally asked Ramsey and Colonel Walter Stewart to hold off the British while he arranged the main line of

defense. The two officers agreed and Wayne deployed their soldiers in a nearby

wood. As the Brigade of Guards came up to their hidden position, the

Americans opened fire into their flank. The Guards charged and cleared the wood

after a tough fight in which they lost 40 casualties including Colonel Henry

Trelawney wounded. Stewart was shot and carried off. The retreating Americans

were set upon in the open by a troop of the 16th Light Dragoons. A dragoon rode up to the unhorsed Ramsey and fired at

him with his pistol. The weapon misfired and Ramsey attacked the trooper with

his sword, dragged him from his horse, and tried to ride away.

Surrounded by dragoons, Ramsey was badly wounded and left for

dead. Later, the British picked him up as a prisoner. Impressed by his bravery,

the British commander Sir Henry Clinton paroled

Ramsey the next day. Ramsey was not exchanged until December 1780.

The Battle of Germantown was a major engagement

in the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War. It was fought on October 4, 1777,

at Germantown, Pennsylvania, between the British Army led by

Sir William Howe, and the American Continental Army, with the 2nd Canadian Regiment, under George Washington.

After defeating the Continental Army at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, and the Battle of Paoli on September

20, Howe outmaneuvered Washington, seizing Philadelphia, the capital of

the United States, on September 26.

Howe left a garrison of some 3,000 troops in Philadelphia, while

moving the bulk of his force to Germantown, then an outlying community to the

city. Learning of the division, Washington determined to engage the British.

His plan called for four separate columns to converge on the British position

at Germantown. The two flanking columns were composed of 3,000 militia, while the

center-left, under Nathanael Greene, the center-right

under John Sullivan, and the reserve under Lord Stirling were made up of regular troops. The ambition behind the

plan was to surprise and destroy the British force, much in the same way as

Washington had surprised and decisively defeated the Hessians at Trenton. In Germantown,

Howe had his light infantry and the 40th Foot spread across

his front as pickets. In the main camp, Wilhelm von Knyphausen commanded the British left, while Howe himself personally

led the British right.

A heavy fog caused a great deal of confusion among the

approaching Americans. After a sharp contest, Sullivan's column routed the

British pickets. Unseen in the fog, around 120 men of the British 40th Foot

barricaded the Chew Mansion. When the American reserve moved forward, Washington

made the erroneous decision to launch repeated assaults on the position, all of

which failed with heavy casualties. Penetrating several hundred yards beyond

the mansion, Sullivan's wing became dispirited, running low on ammunition and

hearing cannon fire behind them. As they withdrew, Anthony Wayne's division

collided with part of Greene's late-arriving wing in the fog. Mistaking each

other for the enemy, they opened fire, and both units retreated. Meanwhile,

Greene's left-center column threw back the British right. With Sullivan's

column repulsed, the British left outflanked Greene's column. The two militia

columns had only succeeded in diverting the attention of the British, and had

made no progress before they withdrew.

Despite the defeat, France, already impressed by the American

success at Saratoga, decided to lend greater aid to the Americans. Howe did not

vigorously pursue the defeated Americans, instead turning his attention to

clearing the Delaware River of obstacles at Red Bank and Fort Mifflin. After unsuccessfully attempting to draw Washington into combat at White Marsh, Howe withdrew to Philadelphia. Washington, his army intact,

withdrew to Valley Forge, where he wintered and re-trained his forces.

Prison labourers and other prisoners of the British

American

prisoners were housed in other parts of the British Empire. Over 100 prisoners

were employed as slave labourers in coal mines in Cape

Breton, Nova Scotia –

they later chose to join the British Navy to secure their freedom. Other

American prisoners were kept in England (Portsmouth, Plymouth, Liverpool, Deal,

and Weymouth), Ireland, and Antigua. By late 1782 England and Ireland housed

over 1,000 American prisoners, who, in 1783, were moved to France prior to

their eventual release.

Continental

Army prisoners of

war from Cherry

Valley were held

by Loyalists at Fort Niagara near Niagara

Falls, New York and

at Fort Chambly near Montreal

During the

war, at least 16 hulks, including the infamous HMS Jersey, were placed by British authorities in the waters of Wallabout Bay off the shores of Brooklyn,

New York as a

place of incarceration for many thousands of American soldiers and sailors from

about 1776 to about 1783. The prisoners of war were harassed and abused by

guards who, with little success, offered release to those who agreed to serve

in the British Navy. Over 10,000 American prisoners of war died from

neglect. Their corpses were often tossed overboard but sometimes were buried in

shallow graves along the eroding shoreline.

Many of the

remains became exposed or were washed up and recovered by local residents over

the years and later interred nearby in the Prison

Ship Martyrs' Monument at Fort Greene Park, once the scene of a portion of the Battle

of Long Island. Survivors

of the British Prison Ships include the poet Philip Freneau, Congressmen Robert Brown and George

Mathews. The latter was

involved in extensive advocacy efforts to improve the prison conditions on the

ships

The American Revolution was an expensive war,

and lack of money and resources led to the horrible conditions of British

prison ships. The climate of the South worsened the difficult conditions. The

primary cause of death in prison ships was diseases, as opposed to starvation.

The British lacked decent and plentiful medical supplies for their own soldiers

and had even less reserved for prisoners. Offshore in the North,

conditions on prison ships caused many prisoners to enlist in the British

military to save their lives. Most American POWs who survived incarceration

were held until late 1779, when they were exchanged for British POWs.[ Prisoners

who were extremely ill were often moved to hospital ships, but poor supplies

precluded any difference between prison and hospital ships.

The British Ship Jersey lists a Josh Peck in the 1779 Muster.

The dates of 1779, connect with the records of

service of Joshua Peck of 3rd Regiment.

Prisoners were returned to England, although

records are very rare. This report was

in Hereford Journal 19th June 1783

Maryland and the

Revolutionary War

The Province of Maryland had

been a British / English colony

since 1632, when Sir George Calvert, first Baron of Baltimore and Lord Baltimore (1579-1632), received a

charter and grant from King Charles I of

England and first created a haven for English Roman Catholics in the New World, with his son, Cecilius Calvert (1605-1675),

the second Lord Baltimore equipping and sending over the first colonists to

the Chesapeake Bay region

in March 1634. The first signs of rebellion against the mother country occurred

in 1765, when the tax collector Zachariah Hood was injured while landing

at the second provincial capital of Annapolis docks,

arguably the first violent resistance to British taxation in the colonies.

After a

decade of bitter argument and internal discord, Maryland declared itself a

sovereign state in

1776. The province was one of the Thirteen Colonies of British America to declare independence from Great Britain and joined the others in

signing a collective Declaration of Independence that summer in the Second Continental Congress in nearby Philadelphia. Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton signed on Maryland's behalf.

Although

no major Battles of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) occurred in Maryland itself

(although the British Royal Navy fleet passed through and up

the Bay to land troops at the "Head of Elk"), to attack the colonies'

capital city, this did not prevent the state's soldiers from distinguishing

themselves through their service. General George Washington counted the "Maryland Line" regiment who fought in the Continental Army especially the famed "Maryland 400" during the Battle of Brooklyn in

August 1776, outside New York Town as

among his finest soldiers, and Maryland is still known as "The Old Line

State" today.

During

the war itself, Baltimore Town served as the temporary capital of the colonies

when the Second Continental Congress met there during December 1776 to February

1777, after Philadelphia had

been threatened with occupation by the British "Redcoats". Towards

the end of the struggle, from November 26, 1783, to June 3, 1784, the state's

capital Annapolis, briefly served as the capital of the fledgling confederation

government (1781-1789) of the United States of America, and it was in the Old Senate Chamber of the Maryland State House on State Circle in Annapolis that

General George Washington famously

resigned his commission as commander in chief of

the Continental Army on December 23, 1783. It was also there that the Treaty of Paris,

which ended the Revolutionary War, was ratified by the Confederation Congress on

January 14, 1784.

Like

other states, Maryland was bitterly divided by the war; many Loyalists refused to join the

Revolution, and saw their lands and estates confiscated as a consequence.

The Barons Baltimore,

who before the war had exercised almost feudal power in Maryland, were

among the biggest losers. Almost the entire political elite of the province was

overthrown, replaced by an entirely new political class, loyal to a new

national political structure.

The

State of Maryland began as the Province of Maryland,

an English settlement in North America founded in 1632 as a proprietary colony. George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore (1580–1632), wished to

create a haven for his fellow English Catholics in the New World. After

founding a colony in the Newfoundland called

"Avalon",

he convinced the King to grant him a second territory in more southern

temperate climes. When George Calvert died in 1632 the grant was transferred to

his eldest son Cecil.

The

ships The Ark and The Dove sent by Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore (1605–1675), landed on

March 25, 1634, at Blackistone Island,

thereafter known as St. Clement's Island.

Here at St. Clement's Island,

led by Father Andrew White,

they raised a large cross, and held a mass. In April 1634, Lord Baltimore's

younger brother Leonard Calvert, first colonial governor, made a

settlement at what was named "St. Mary's City".

Religious strife

Although

Maryland was an early pioneer of religious toleration in the British colonies,

religious strife among Anglicans, Puritans, Roman Catholics, and Quakers was common in the early

years, and in 1644 Puritan rebels briefly seized control of the province.

Economy

Diagram

of a slave ship from

the Atlantic slave trade.

From an Abstract of Evidence delivered before a select committee of

the House of Commons of Great Britain in 1790 and 1791.

See

also: History of slavery in Maryland

Despite

early competition with the colony of Virginia to its south, the Province

of Maryland developed along lines very similar to those of Virginia. Its early

settlements and populations centres tended to cluster around the rivers and

other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Like Virginia, Maryland's

economy quickly became centered around the farming of tobacco for sale in Europe. The

need for cheap labour to help with the growth of tobacco, and later with the

mixed farming economy that developed when tobacco prices collapsed, led to a

rapid expansion of indentured servitude and,

later, forcible immigration and enslavement of

Africans.

In the

later colonial period, the southern and eastern portions of the Province

continued in their tobacco economy, heavily dependent on slave labour, but as

the revolution approached, northern and central Maryland increasingly became

centres of wheat production. This helped drive the expansion of interior

farming towns like Frederick and

Maryland's major port city of Baltimore.

Economic tensions

See

also: Tobacco Lords and Tobacco in the American Colonies

Among

the many tensions between Maryland and the mother country were economic

problems, focused around the sale of Maryland's principle cash crop, tobacco. A

handful of Glasgow tobacco merchants increasingly dominated the tobacco trade

between Britain and her colonies, manipulating prices and causing great

distress among Maryland and Virginia planters, who by the time of the outbreak

of war had accumulated debts of around £1,000,000, a huge sum at the time.

These debts, as much as the taxation imposed

by Westminster, were among the colonists' most bitter grievances.

Prior to

1740, Glasgow merchants were responsible for the import of less than 10% of

America's tobacco crop, but by the 1750s a handful of Glasgow Tobacco Lords handled more of the trade

than the rest of Britain's ports combined. Heavily capitalised, and taking

great personal risks, these men made immense fortunes from the "Clockwork

Operation" of fast ships coupled with ruthless dealmaking and the

manipulation of credit. Maryland planters were offered easy credit by the

Glaswegian merchants, enabling them to buy European consumer goods and other

luxuries before harvest time gave them the ready cash to do so. But, when the

time came to sell the crop, the indebted growers found themselves forced by the

canny traders to accept low prices for their harvest simply in order to stave

off bankruptcy.

In

neighbouring Virginia, tobacco planters experienced similar problems. At

his Mount Vernon plantation,

future President of the United States George Washington saw his liabilities swell

to nearly £2000 by the late 1760s. Thomas Jefferson, on the verge of losing his own

farm, accused British merchants of unfairly depressing tobacco prices and

forcing Virginia farmers to take on unsustainable debt loads.

In 1786,

he remarked:

A

powerful engine for this [mercantile profiting] was the giving of good prices

and credit to the planter till they got him more immersed in debt than he could

pay without selling lands or slaves. They then reduced the prices given for his

tobacco so that ... they never permitted him to clear off his debt.

Many

Marylanders sought to use the opportunity posed by war to repudiate their

debts. One of the "Resolves" later adopted by the citizens of

Annapolis on May 25, 1774, would read as follows:

Resolved,

that it is the opinion of the meeting, that the gentlemen of the law of this

province bring no suit for the recovery of any debt, due from any inhabitant of

this province to any inhabitant of Great Britain, until the said act [The Stamp

Act] be repealed

After

the war, few of the enormous debts owed by the colonists would ever be repaid.

There

were also serious tensions between the colonists and the British over land,

especially after the Crown effectively confirmed Indian land rights in 1763.

Washington himself was appalled by this decision to protect native property

rights, writing to his future partner William Crawford in

1767 that he: could never look upon that Proclamation in any other light ...

than as a temporary expedient to quiet the minds of the Indians. It must fall,

of course, in a few years, especially when those Indians consent to our

occupying their lands.

In 1764

Britain imposed a tax on sugar,

the first of many ultimately unsuccessful attempts to make her North American

subjects bear a portion of the cost of the recent French and Indian war.

The first stirrings of revolution in Maryland came in the Fall of 1765, when

the speaker of the Lower House of the Maryland General Assembly received a

number of letters from Massachusetts, one proposing a meeting of delegates from

all the colonies, others objecting to British taxation without consent and

proposing that Marylanders should be "free of any impositions, but such as

they consent to by themselves or their representatives".

Charles Carroll of Carrollton

Maryland

planter Charles Carroll of Carrollton was the only Roman Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence.

One of

the early voices for independence in Maryland was the wealthy Roman Catholic planter Charles Carroll of Carrollton. In 1772 he engaged in a debate conducted through

anonymous newspaper letters and maintained the right of the colonies to control

their own taxation. As a Roman Catholic, he was barred from entering politics,

from practicing law, and from voting.

In the

early 1770s, Carroll appears to have begun to embrace the idea that only

violence could break the impasse with Great Britain. According to legend,

Carroll and Samuel Chase (who

would also later sign the Declaration of Independence on Maryland's behalf) had

the following exchange:

Chase:

"We have the better of our opponents; we have completely written them

down."

Carroll: "And do you think that writing will settle the question between

us?"

Chase: "To be sure, what else can we resort to?"

Carroll: "The bayonet. Our arguments will only raise the feelings of the

people to that pitch, when open war will be looked to as the arbiter of the

dispute".

Writing

in the Maryland Gazette under

the pseudonym "First Citizen," Carroll became a prominent spokesman

against the governor's proclamation increasing legal fees to state officers and

Protestant clergy. Carroll also served on various Committees of Correspondence, promoting independence.

From

1774 to 1776, Carroll was a member of the Annapolis Convention.

He was commissioned with Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Chase and his cousin John Carroll in

February 1774 to seek aid from Canada. He was a member of

Annapolis' first Committee of Safety in 1775. In early 1776,

while not yet a member, the Congress sent him on a mission to Canada. When

Maryland decided to support the open revolution, he was elected to the

Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and remained a delegate until 1778. He

arrived too late to vote in favor of it, but was able to sign the Declaration of Independence.

It is

possible that the First Amendment to

the United States Constitution -

guaranteeing freedom of religion - was written in appreciation for Carroll's

considerable financial support during the Revolutionary War.

Carroll was the only Roman Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence,

and until his death in 1832 he was its last living signatory.

Samuel Chase

Samuel

Chase, firebrand revolutionary and later a justice of the United States Supreme Court.

Samuel Chase (1741–1811),

was a "firebrand" states-righter and revolutionary, and was a

signatory to the United States Declaration of

Independence as

a representative of Maryland. He co-founded Anne Arundel County's Sons of Liberty chapter with his close

friend William Paca,

and led opposition to the 1765 Stamp Act. Later he became an Associate Justice

of the United States Supreme Court.

Loyalist opposition

Daniel

Dulaney the Younger proposed "a legal, orderly, and prudent

resentment" rather than war.

One

prominent Loyalist was Daniel Dulaney the Younger, Mayor of Annapolis,

and an influential lawyer in the period immediately before the Revolution.

Dulany was a noted opposer of the Stamp Act 1765, and wrote the noted

pamphlet Considerations on

the Propriety of Imposing Taxes in the British Colonies which argued against taxation without representation. The pamphlet has been described

as "the ablest effort of this kind produced in America". In the

pamphlet, Dulany summarized his position as follows: "There may be a time

when redress may not be obtained. Till then, I shall recommend a legal,

orderly, and prudent resentment".Eventually, as war became inevitable,

Dulany (like many others) found his essentially moderate position untenable and

he found himself forced to choose sides. Dulany was not able to rebel against

the Crown he and his family had served so long. He believed that protest rather

than force should furnish the solution to America's problems, and that legal

process, logic, and the "prudent" exercise of "agreements"

would eventually prevail upon the British to concede the colonists' demands.

Coming of Revolution

In

1774, committees of correspondence sprung up throughout the colonies, offering

support to Boston, Massachusetts,

after the British closed the port and increased the occupying military force.

Massachusetts had asked for a general meeting or Continental Congress to

consider joint action by all the colonies. To forestall any such action, the

royal governor of Maryland, Sir Robert Eden prorogued the

Maryland colonial assembly on April 19, 1774. This was the last session of the

colonial assembly ever held in Maryland.

Painting

by Francis Blackwell Mayer,

1896, depicting the burning of the Peggy Stewart at

the Annapolis Tea Party, October 19, 1774.

On

October 19, 1774, the Peggy Stewart,

a Maryland cargo vessel, was set alight and burned by an angry mob in

Annapolis, punishing the ship's captain for contravening the boycott on tea imports and mimicking the events of the more

famous Boston Tea Party in

December 1773. This event has since become known as the "Annapolis Tea

Party".

In May

1774, according to local legend, the Chestertown Tea Party took

place in Chestertown, Maryland,

during which Maryland patriots boarded the brigantine Geddes in broad daylight

and threw its cargo of tea into the Chester River, as a protest against taxes

imposed by the British Tea Act. The event is still celebrated

to this day each Memorial Day weekend with a festival and

historic re-enactment known as the Chestertown Tea Party Festival.

Governor

Eden returned to Maryland from England shortly after the Peggy Stewart was

burned. On December 30, 1774, he wrote:

The

spirit of resistance against the Tea Act, or any mode of internal

taxation, is as strong and universal here as ever. I firmly believe that they

will undergo any hardship sooner than acknowledge a right in the British Parliament in

that particular, and will persevere in their non-importation and

non-exportation experiments, in spite of every inconvenience that they must

consequently be exposed to, and the total loss of their trade.

Despite

such protests, and a growing sense that war was inevitable, Maryland still held

back from full independence from Great Britain, and gave instructions to that

effect to its delegates to the First Continental Congress which met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in September 1774.

Assembly of Freemen

Thomas Johnson,

Maryland's first elected governor under its 1776 Constitution.

During

this initial phase of the Revolutionary period, Maryland was governed by

the Assembly of Freemen,

an Assembly of the state's counties.

The first convention lasted four days, from June 22 to June 25, 1774. All

sixteen counties then existing were represented by a total of 92 members; Matthew Tilghman was elected chairman.

The

eighth session decided that the continuation of an ad-hoc government by the

convention was not a good mechanism for all the concerns of the province. A

more permanent and structured government was needed. So, on July 3, 1776, they

resolved that a new convention be elected that would be responsible for drawing

up their first state constitution,

one that did not refer to parliament or the king, but would be a

government "...of the people only." After they set

dates and prepared notices to the counties they adjourned. On August 1, all

freemen with property elected delegates for the last convention. The ninth and

last convention was also known as the Constitutional

Convention of 1776.

They drafted a constitution, and when they adjourned on November 11, they would

not meet again. The Conventions were replaced by the new state government which

the Maryland Constitution of 1776 had established. Thomas Johnson became

the state's first elected governor.

Declaration of

Independence

Maryland declared independence

from Britain in

1776, with Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton signing the Declaration of Independence for the colony.

In 1777,

all Maryland voters were required to take the Oath of Fidelity and Support. This was an oath swearing allegiance to the state

of Maryland and denying allegiance and

obedience to Great Britain.

As enacted by the Maryland General Assembly in 1777, all persons holding any office of

profit or trust, including attorneys at law, and all voters were required to

take the oath no later than March 1, 1778. It was signed by 3,136

residents of Montgomery and Washington counties.

On March

1, 1781, the Articles of Confederation took effect with Maryland's ratification. The

articles had initially been submitted to the states on November 17, 1777, but

the ratification process dragged on for several years, stalled by an interstate

quarrel over claims to uncolonised land in the west. Maryland was the last

hold-out; it refused to ratify until Virginia and New York agreed to rescind

their claims to lands in what became the Northwest Territory.

Maryland

would later accept the United States Constitution more readily, ratifying it on April 28, 1788.

Although

no major Battles of the American Revolutionary

War occurred

in Maryland, this did not prevent the state's soldiers from distinguishing

themselves through their service. General George Washington was impressed with the

Maryland regulars (the "Maryland Line") who fought in the Continental Army and, according to one

tradition, this led him to bestow the name "Old Line State" on

Maryland.

The state also filled other roles during the

war. For instance, the Continental Congress met

briefly in Baltimore from December 20, 1776,

through March 4, 1777. Baltimore served as the temporary capital of the

colonies when the Second Continental Congress met there during December 1776 to February

1777, (when Philadelphia was occupied by the British, meeting at the old "Henry Fite House", a substantial

three-and-half story brick structure on the western edge of town (beyond the

possible cannon range of any British Royal Navy ships that might try to

force a passage upstream on the Patapsco River from the Chesapeake Bay to the Harbor),

The

building was later a tavern/hotel, then named "Congress Hall" after the sessions held

there at Market Street (previously Long Street and later West Baltimore Street)

and South Sharp-and later North Liberty Street.

Marylander John Hanson served as President of the Continental Congress from 1781 to 1782. Hanson

was the first person to serve a full term as President of the Congress under

the Articles of Confederation. From November 26, 1783, to June 3, 1784,

Annapolis served as the United States capital and the Confederation Congress

met in the Maryland State House.

(Annapolis was a candidate to become the new nation's permanent capital

before Washington, D.C. was

built). It was in the old senate chamber[ that George Washington

resigned his commission as commander in chief of the Continental Army on December 23, 1783.

It was also there that the Treaty of Paris,

which ended the Revolutionary War, was ratified by Congress on January 14,

1784.

Loyalists and the war

Main

article: Loyalist (American Revolution)

Sir Robert Eden,

last colonial Governor of Maryland

During

the war many Marylanders, such as Benedict Swing

On May

13, 1777 Benedict Swingate Calvert was forced to resign his position as Judge

of the Land Office, and, as the conflict grew,

he became fearful of his family's safety, writing in late 1777 that his family

"has been made so uneasy by these frequent outrages" that he wished

to "remove my family and property where I can get protection".

Calvert

did not leave Maryland, nor did he involve himself in the fighting, though he

did on occasion supply the Continental Army with food and provisions. After the war, he

had to pay triple taxes as did other Loyalists, but he was never forced to sign

the loyalty oath and his lands and property

remained unconfiscated.

African Americans and

the war

The

principal cause of the American Revolution was liberty, but only on

behalf of white men, and certainly not slaves. The British, desperately short

of manpower, sought to enlist African American soldiers to fight on behalf of

the Crown, promising them liberty in exchange.

As a result

of the looming crisis in 1775 the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation that promised freedom to

servants and slaves who were able to bear arms

and join his Loyalist Ethiopian Regiment:

... I do

require every Person capable of bearing Arms, to resort to His MAJESTY'S

STANDARD, or be looked upon as Traitors to His MAJESTY'S Crown and Government,

and thereby become liable to the Penalty the Law inflicts upon such Offenses;

such as forfeiture of Life, confiscation of Lands, &. &. And I do

hereby further declare all indented Servants,

Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) free that are able and willing to

bear Arms, they joining His MAJESTY'S Troops as soon as may be, for the more

speedily reducing this Colony to a proper Sense of their Duty, to His MAJESTY'S

Crown and Dignity.

— Lord Dunmore's Proclamation, November 7, 1775

About

800 men joined up; some helped rout the Virginia militia at the Battle of Kemp's

Landing and

fought in the Battle of Great Bridge on the Elizabeth River, wearing the motto "Liberty

to Slaves", but this time they were defeated. The remains of their

regiment were then involved in the evacuation of Norfolk,

after which they served in the Chesapeake area. Unfortunately the

camp that they had set up there suffered an outbreak of smallpox and

other diseases. This took a heavy toll, putting many of them out of action for

some time. The survivors joined other British units and continued to serve

throughout the war.

Blacks

were often the first to come forward to volunteer and a total of 12,000 blacks

served with the British from 1775 to 1783. This factor had the effect of

forcing the rebels to also offer freedom to those who would serve in the

Continental army. Such promises were often reneged upon by both sides.

In

general though, the war left the institution of slavery largely unaffected, and

the prosperous life of Maryland planters continued.

After the war

The

Official flag of the State of Maryland still retains the arms of the Calvert family, the Barons Baltimore.

In

1783, Henry Harford, the last proprietarial governor

of Maryland and the illegitimate son of Frederick Calvert, 6th

Baron Baltimore,

attempted to recover his estates in Maryland which had been confiscated during

the American Revolution, where he was a witness to George Washington's resignation of command at Annapolis. He and

Governor Eden were

invited to stay at the home of Dr. Upton Scott and his nephew, Francis Scott Key. However, he had no success in retrieving his land,

in spite of the fact that Charles Carroll of

Carrollton and Samuel Chase argued

in his favour. In 1786, the case was decided by the Maryland General Assembly. Although it passed in the

House, the Senate unanimously rejected it. In their reasoning for this

rejection, the Senate cited Henry's absence during the war, and his father

Frederick's alienation of his subjects, as major factors.

Returning

to Britain, he claimed compensation through the English courts and was awarded

£100,000.

Some

trace of the Calvert family's proprietarial rule in Maryland

still remains. Frederick County,

Maryland, is

named after the last Baron Baltimore, and the official flag of the State of

Maryland, uniquely among the 50 states, bears witness to their family legacy.

1.

^ Presumably, part of the

regiment was detached with Ramsey, but this is not directly stated by the

source.

References[edit]

1.

^ Jump up to:a b Boatner,

Mark M. III (1994). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. p. 436. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

2.

^ Wright, Robert K. Jr. (1983). "Lineage". The Continental

Army. United States Army

Center of Military History.

pp. 277–280. CMH Pub 60-4. Retrieved 28

May 2006.

3.

^ McGuire, Thomas J. (2006). The Philadelphia

Campaign, Volume I. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books. p. 217. ISBN 0-8117-0178-6.

4.

^ McGuire, Thomas J. (2006). The Philadelphia

Campaign, Volume I. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books. p. 171. ISBN 0-8117-0178-6.

5.

^ McGuire, Thomas J. (2006). The Philadelphia

Campaign, Volume I. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books.

pp. 220–223. ISBN 0-8117-0178-6.

6.

^ McGuire, Thomas J. (2006). The Philadelphia

Campaign, Volume I. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books. p. 224. ISBN 0-8117-0178-6.

7.

^ Morrissey, Brendan (2008). Monmouth Courthouse

1778: The last great battle in the North. Long Island City, N.Y.: Osprey

Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-84176-772-7.

8.

^ Boatner, Mark M. III (1994). Encyclopedia of

the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books.

p. 912. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

9.

^ Morrissey, Brendan (2008). Monmouth Courthouse

1778: The last great battle in the North. Long Island City, N.Y.: Osprey

Publishing. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-84176-772-7.

10.

^ Morrissey, Brendan (2008). Monmouth Courthouse

1778: The last great battle in the North. Long Island City, N.Y.: Osprey

Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-84176-772-7.

11.

^ Morrissey, Brendan (2008). Monmouth Courthouse

1778: The last great battle in the North. Long Island City, N.Y.: Osprey

Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-84176-772-7.

12.

^ Morrissey, Brendan (2008). Monmouth Courthouse

1778: The last great battle in the North. Long Island City, N.Y.: Osprey Publishing.

p. 56. ISBN 978-1-84176-772-7.

Further reading[edit]

·

Balch, Thomas

(1857). Papers Relating Chiefly to the Maryland Line During the

Revolution. Philadelphia. p. 218 pgs.

·

Christian,

Bernard (1972) [1900]. Muster Rolls &

other Records of Service of Maryland Troops in the American Revolution

1775-1783 ((HTML)) (Reprint

ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Lord Baltimore Press, Maryland Historical Society.

p. 736 pgs. Retrieved 29

May 2006.

·

McGuire,

Thomas J. (2007). The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume II. Mechanicsburg,

Penn.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0206-5.

·

Bibliography of the

Continental Army in Maryland compiled by the United States Army Center of Military

History

No comments:

Post a Comment